Focus on Spanish Society. May 2025

Fecha: mayo 2025

Inmigración, Inmigración irregular, España.

Section I. Spain in Europe

I.1. Fragmented geography of asylum in the EU

2024 is the second consecutive year that Spain ranks second in volume, a position it has consistently maintained—either second or third— since 2019

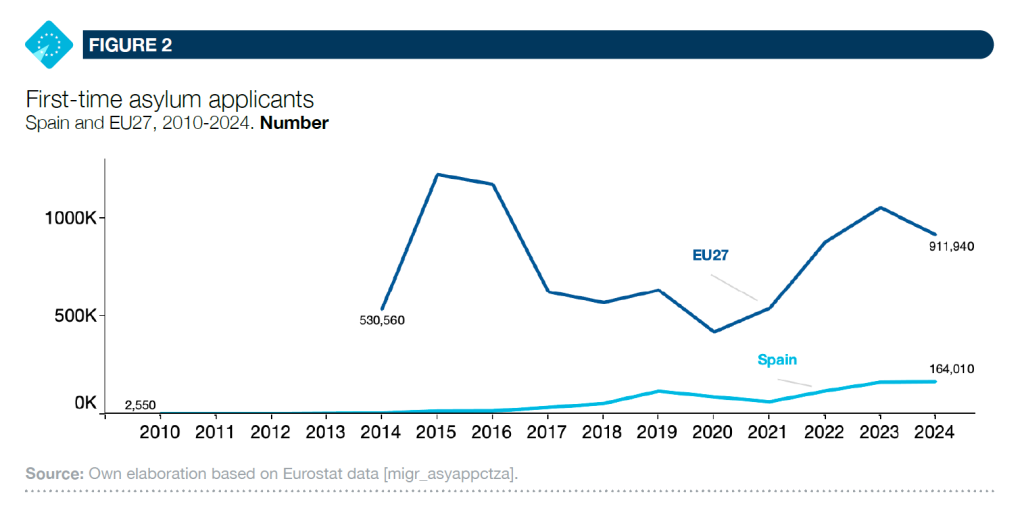

In 2024, the European Union registered nearly one million first-time asylum applications (912,000), marking a 13 % decrease compared to 2023. Germany remained the main destination, accounting for one in four applications, while Spain held its position as the second-largest host country in the EU27, with 18 % of the total (164,000)—slightly ahead of Italy (151,000) and France (130,000) (Figure 1). This marks the second consecutive year that Spain ranks second in volume, a position it has consistently maintained—either second or third—since 2019. Although asylum applications have risen sharply across the EU since the COVID-19 years, their distribution remains highly uneven. Eastern and Central European countries such as Hungary (25 applications), Slovakia (135), and Lithuania (295) played a minimal role in asylum reception. This long-standing imbalance has become increasingly entrenched, fueling ongoing debates over solidarity and responsibility-sharing within the EU, as evidenced by a recent ruling by a top German court, which authorized the return of asylum seekers to Greece.1

Spain’s rise as the second-largest recipient of asylum seekers is particularly notable. Over the past decade, Spain’s numbers have grown steadily—even as EU trends fluctuated due to crises such as the Syrian war (Figure 2). While 2015 marked a dramatic spike in asylum claims across Europe, Spain experienced a more gradual growth, reaching its highest-ever figure in 2024.

Germany continues to receive the highest number of asylum applications from individuals fleeing geopolitical conflict zones

Data from 2024 confirm sharp divergences in the national profiles of asylum seekers across EU countries. Germany continues to receive the highest number of asylum applications from individuals fleeing geopolitical conflict zones, particularly Syrians (33 % of all first-time applications in Germany), Afghans (15 %), and Turks (13 %) (Figure 3). This concentration is further underscored by the fact that a majority of applicants from these nationalities chose Germany as their destination: 62 % of all Turkish asylum seekers in the EU applied in Germany, along with 52 % of Syrians and 47 % of Afghan (Figure 4). The second most common destination for Syrians and Afghans was Greece, receiving 15 % and 21 % of their respective applications. For Turkish applicants, the second destination was France (13 %), which is also notable for receiving more than half (53 %) of all applications from Ukrainian nationals. Italy, in contrast, has become the primary destination for asylum seekers from Bangladesh, with 80 % of those who applied in the EU submitting their claims there. It is also the main recipient of asylum applications from Peru, with 58 % of Peruvians applying in Italy rather than Spain.

In 2024, Spain stood out as the main European destination for Latin American asylum seekers, particularly from Venezuela and Colombia

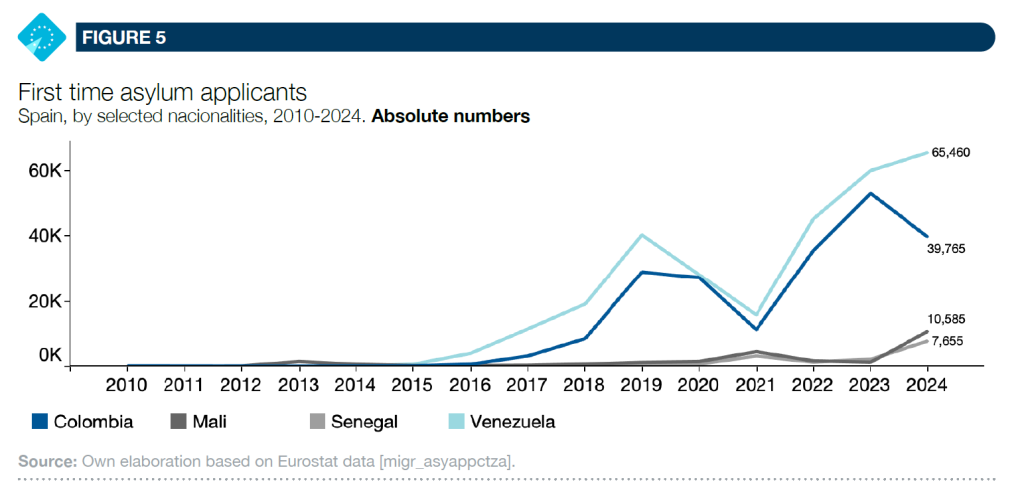

Spain’s asylum landscape is markedly different from that of other EU countries, with a strong regional concentration. In 2024, it stood out as the main European destination for Latin American asylum seekers, particularly from Venezuela (40 % of first-time applications in Spain), Colombia (24 %), and, to a lesser extent, Peru (6 %) (Figure 3). The 65,000 applications from Venezuelans and 40,000 from Colombians accounted for 90 % and 79 %, respectively, of all first-time applications from those nationalities across the EU (Figure 4).

Most of applicants from Mali and Senegal submitted their claims in Spain in 2024, highlighting the country’s growing importance along specific migration routes

Beyond Latin America, Spain also emerged in 2024 as a key destination for asylum seekers from certain West African countries. Notably, 64 % of applicants from Mali and 60 % from Senegal submitted their claims in Spain (Figure 4), highlighting the country’s growing importance along specific migration routes. Although these groups still represent a relatively small share of Spain’s total applications—6 % for Mali and 5 % for Senegal—the sharp increases compared to 2023 (multiplying their numbers by 8.5 and 3.5, respectively) suggest the emergence of a potentially significant trend.

This shift is particularly striking given the historically limited presence of Malian and Senegalese communities in Spain, especially in the case of Mali. In 2023, just prior to the surge in asylum claims (Figure 5), the resident populations from these countries, according to the Population Continuous Statistics, were relatively small—approximately 91,000 people born in Senegal and only 32,000 people born in Mali. By contrast, the rise in asylum applications from Venezuela and Colombia in previous years occurred in a very different context: both countries already had large established communities in Spain before the increase in asylum claims began. In 2015, just before the upsurge in applications, there were around 519,000 people of venezuelan origin and 715,000 individuals born in Colombia living in the country.

Spain’s asylum profile has traditionally appeared less shaped by large-scale, immediate conflict-driven displacements than by linguistic, cultural, and historical ties with Latin America. While it may also be responding to forms of political instability and violence in that region, the response appeared less acute. However, the recent surge in applications from Mali—driven by intensifying conflict—may signal a shift, indicating that Spain’s role in responding to more urgent displacement crises in West Africa could become increasingly prominent.

I.2. Spain’s shift from secondary route to strategic corridor for irregular migration

In 2024, irregular entries fell significantly compared to 2023. This overall decline was largely driven by a sharp reduction in arrivals along the Central Mediterranean route

Irregular entries through the EU’s southern borders have fluctuated considerably over the last decade, following changes in the geopolitical contexts, enforcement efforts, and the strategic repositioning of smuggling networks. In 2024, these entries fell significantly—down 38 % compared to 2023 (Figure 6). This overall decline was largely driven by a sharp reduction in arrivals along the Central Mediterranean route, linked to significantly strengthened efforts to combat migrant smuggling by countries of origin and transit, particularly Tunisia. These measures played a central role in limiting flows toward Italy. At the same time, however, arrivals along the Western Atlantic route—specifically via the Canary Islands—have increased.

In 2024, Italy saw a marked drop in irregular entries, registering 66,617 arrivals—down from a peak of 157,652 in 2023, which had followed a steady increase since 2021. Greece, after years of relatively moderate figures following the peak of the 2016 refugee crisis, experienced a resurgence in 2024, with 62,043 arrivals—its highest since 2019. Spain, by contrast, registered a more gradual increase, reaching 63,970 irregular entries in 2024, its highest level on record and nearly matching the figures for Italy and Greece. This figure is more than double the number recorded in 2006, the year of the so-called “cayucos crisis” in the Canary Islands. Nevertheless, this number remains relatively small when compared to the overall volume of new residents in Spain. Although data for 2024 are not yet available, in 2023 the country registered approximately 1.25 million new residents. If similar trends continue, irregular entries in 2024 would account for only around 5 % of total new arrivals.

Spain presents a markedly different profile from Greece and Italy, with a strong concentration of arrivals from West and North Africa

As happens regarding asylum applications, the national profiles of irregular arrivals vary sharply across the three routes (Figure 7). Italy’s flows are dominated by people from Bangladesh (21 %), Syria (19 %), and Tunisia (12 %), alongside a broad mix of other nationalities (36 %). Greece is still the main entry point for Syrians (34 %) and Afghans (24 %), as well as for smaller shares of Egyptians, Turks, and Eritreans. Spain presents a markedly different profile, with a strong concentration of arrivals from West and North Africa. In 2024, nationals from Mali (27 %), Senegal (20 %), Algeria (16 %), and Morocco (13 %) together represented over three-quarters of all irregular entries into Spain.

Spain’s growing relevance as a corridor for irregular migration is closely linked to the changes observed in its asylum profile. Although irregular entries still represent a small share of the overall inflows, the trend is nonetheless significant as it reflects growing pressure from regions such as the Sahel, where escalating insecurity and violence are driving mobility. In the context of mounting uncertainty in the global geopolitical landscape, this dynamic suggests that Spain is no longer a peripheral route but a central player in Europe’s irregular migration geography.

Section II. Public opinion trends

Spain’s Public Opinion on Immigration Remains Among the Most Positive in Europe

In a context of sustained growth in Spain’s migrant population, public opinion on immigration stands out as notably positive

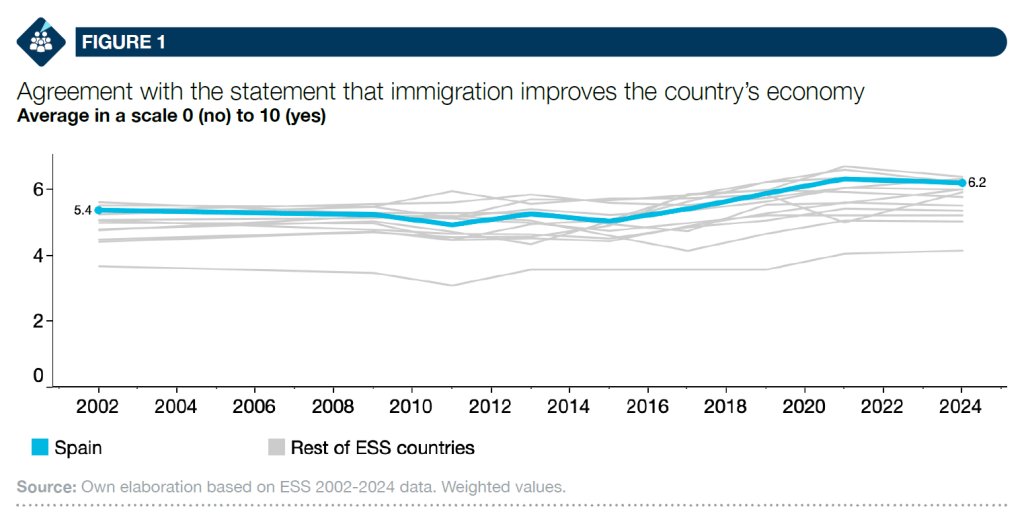

In a context of sustained growth in Spain’s migrant population —averaging around 1.2 million new residents per year over the past two years— it is particularly relevant to examine how public attitudes toward immigration have evolved. According to 2024 data from the European Social Survey (ESS), Spanish public opinion on immigration stands out as notably positive in the European context. When asked whether immigration is good or bad for their country’s economy—on a scale from 0 (very bad) to 10 (very good)—several findings are particularly striking. With the exception of Greece, which consistently reports the most negative views across all indicators, most EU15 countries with available data cluster between average scores of 4.5 to 6.5 (Figure 1). Spain has consistently been among the most positive countries, reaching a score of 6.2 in 2024-one of the highest in the EU. Remarkably, Spain already held the third-highest position as far back as 2002, just behind Sweden and Austria.

Although the trend showed a slight decline until 2013— likely due to the deep economic crisis that began in 2008—Spain’s scores remained close to those of the Scandinavian countries. In fact, this period highlights the remarkable resilience of Spanish public opinion: even during years when unemployment exceeded 25 %, support for immigration remained largely stable.

Even during years when unemployment exceeded 25 %, support for immigration remained largely stable

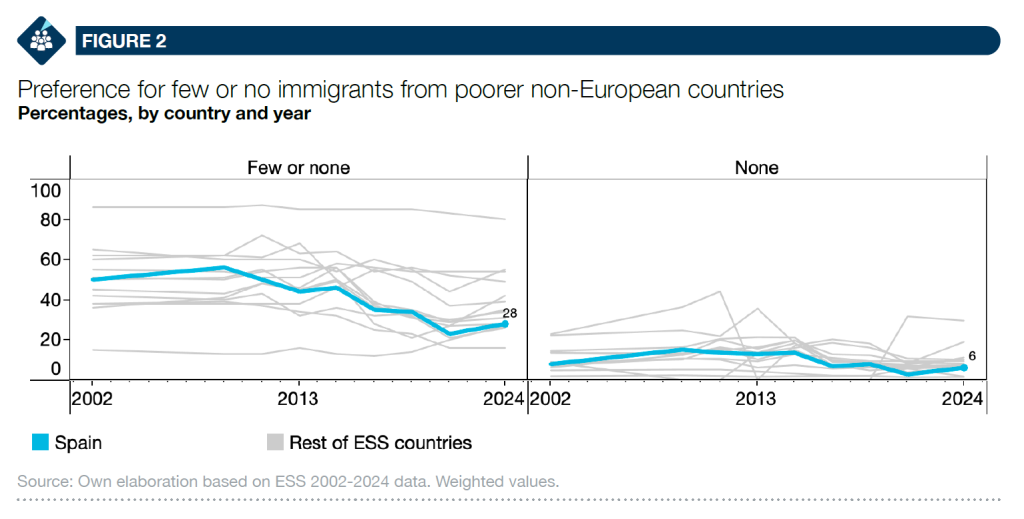

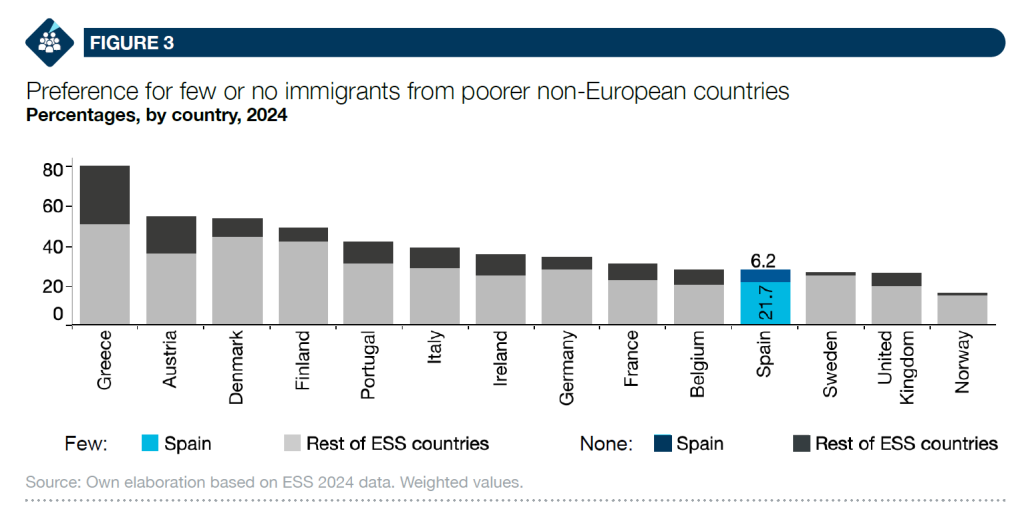

Given the generally positive attitudes, it is worth asking: who in Spain supports restricting immigration flows? In 2002, when Spain still had relatively little experience as a destination country for immigration, 50 % of the population supported allowing either only a few or no immigrants from poor non European countries to settle (Figure 2 - left). Since then, support for restrictive positions has nearly halved, falling to 28 % in 2024. This places Spain among the least restrictive EU countries, behind only Norway (16 %), the United Kingdom (26 %), and Sweden (27 %) (Figure 2 - right).

An even more telling indicator is the proportion of people who believe no immigrants of this type should be allowed at all. In 2009, at the height of the Great Recession, 15 % of Spaniards held this view (Figure 3). By 2024, that number had dropped to just 6 %, making Spain one of the countries with the fewest supporters of total closure—surpassed only by Norway (2 %) and Sweden (2 %).

To understand the social and political underpinnings of this trend, we can look at the relationship between ideology and support for restrictions. When comparing four key years—2002, 2009, 2015, and 2024—a clear pattern emerges: the further to the right respondents place themselves on the ideological scale (0 = left, 10 = right), the more likely they are to favour restrictive immigration policies (Figure 4).

Yet, this general relationship has evolved. In 2009, during the early stages of the economic crisis, nearly 40 % of left-leaning respondents in Spain supported some form of restriction, compared to 70 % among those on the right. By 2024, however, these figures had dropped across the entire spectrum: just over 10 % among those on the left, and around 50 % among those on the right. The most notable decline occurred among left-leaning respondents, who have moved away from restriction more decisively over time.

While support for restriction among left-leaning Spaniards is now in line with the European average, those on the right appear significantly less restrictive

This pattern mirrors trends seen in other European countries included in the survey. However, Spain stands out in one important respect: while support for restriction among left-leaning Spaniards is now in line with the European average, those on the right appear significantly less restrictive. In 2024, just over 50 % of right-leaning respondents in Spain supported restrictions, compared to an average of 68 % among their counterparts in other countries.

Section III. Follow-up social data

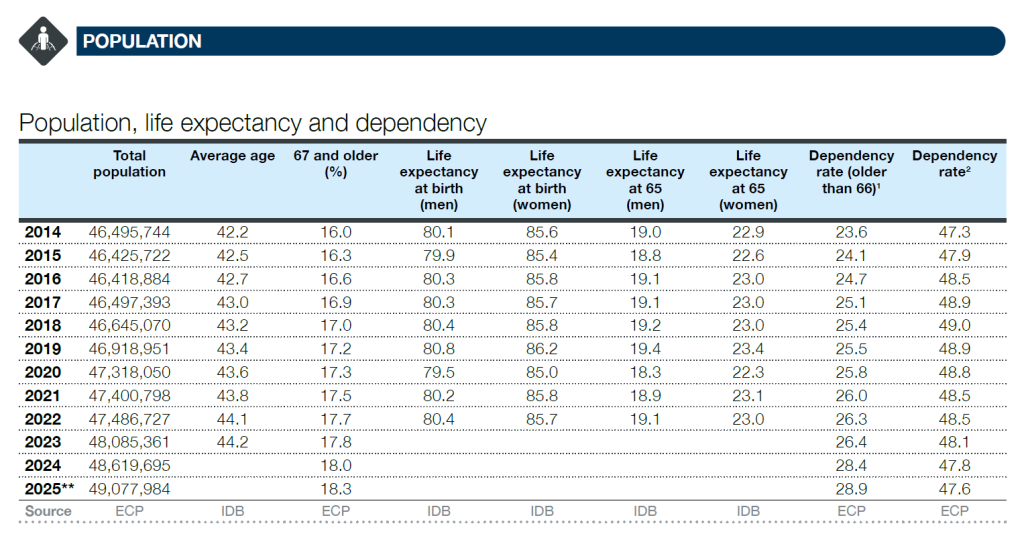

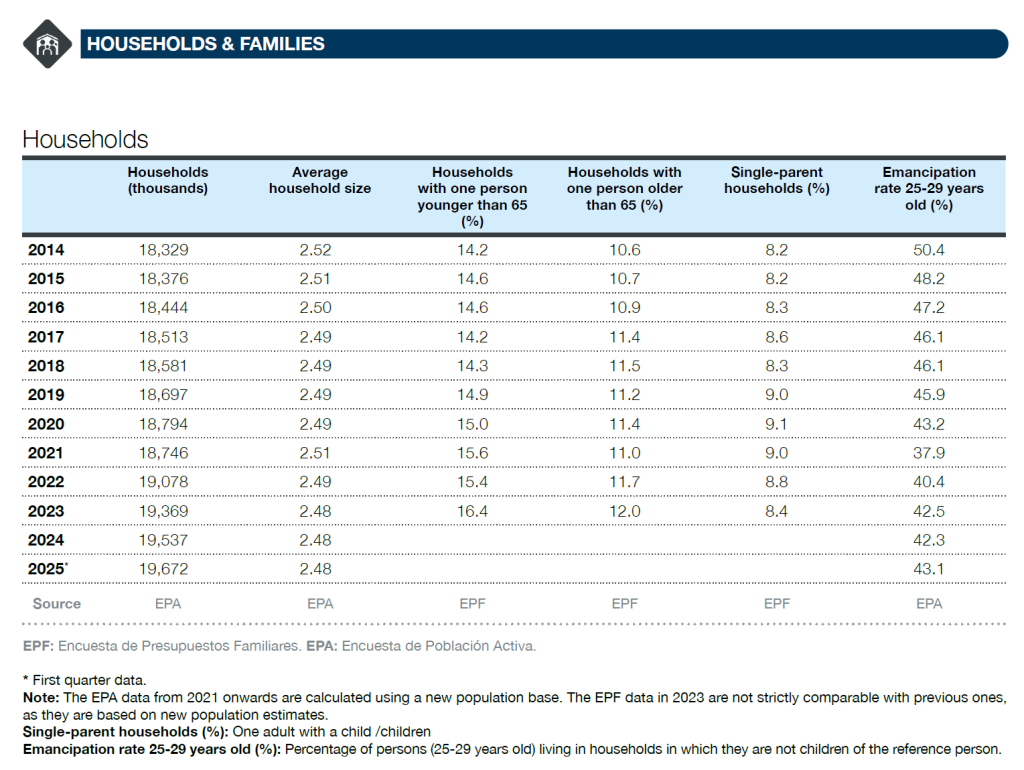

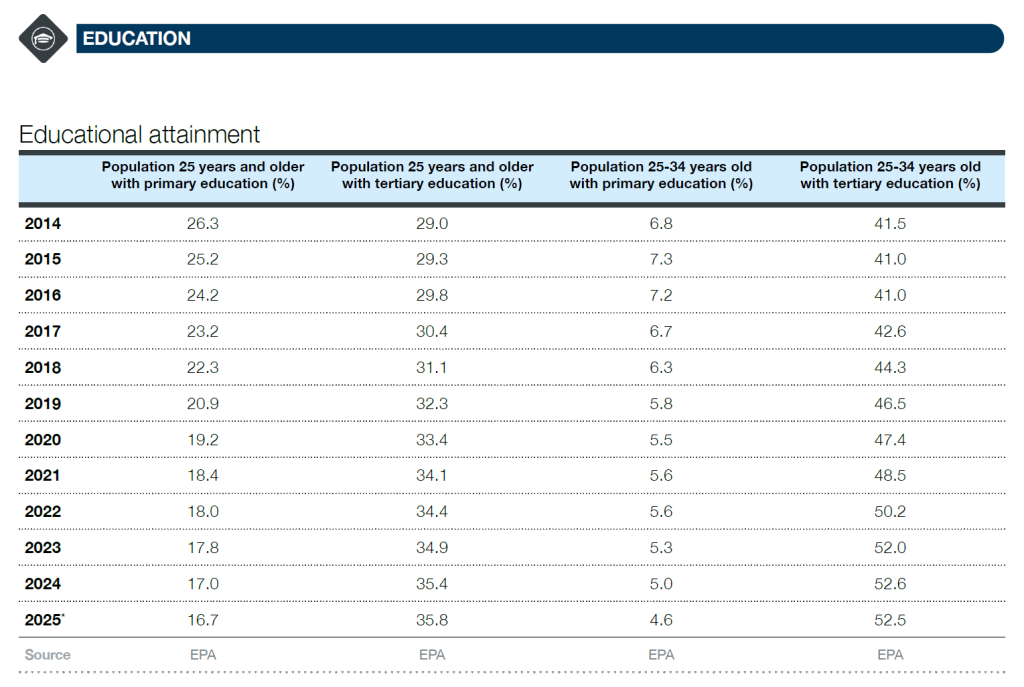

Notes: